Articles & Reports

The Camp at Sand Bar Dam PG&E Cultural Resources

Editor's Note: The following is an article prepared for PG&E as a mitigation for an upcoming project at Sand Bar Dam. Part of that effort is to provide public access to information about the company's camp adjacent to the dam.

The Camp at Sand Bar Dam

The Sand Bar camp is part of a long history of company camps for workers with jobs in very remote locations. In the days before automobiles and good roads, employees needed to live where they worked. Sand Bar Dam is located on the Middle Fork Stanislaus River about 36 miles downstream from the Relief Reservoir and two and a half miles downstream from the Spring Gap Powerhouse. At Sand Bar Flat, jobs included operating the dam, running a saw mill, maintaining the flumes and constructing the tunnels that spread out from this site to carry water farther downstream for power generation.

The importance of the hydroelectric development at Sand Bar lies in its earliest years and association with the Stanislaus Electric Company, not with Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), who bought the completed system in the 1920s. The camp was established around 1909, soon after the first timber crib dam and the Stanislaus Flume were completed. The original camp burned down in 1929 and was replaced by PG&E beginning in 1929 as part of the development of a construction camp. The new buildings were used until 1939, when the Stanislaus Tunnel construction project was complete. After that date use was sporadic at best and the buildings were abandoned in place in the mid-1950s and removed by the late 1960s.

The Spring Gap-Stanislaus Hydroelectric Project

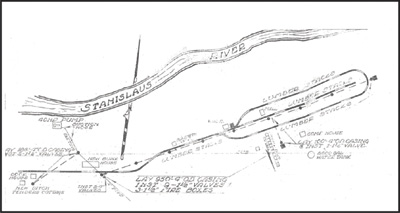

The Sand Bar Dam and its camp are part of the PG&E’s Spring Gap-Stanislaus Hydroelectric Project, a network of reservoirs, powerhouses, dams, ditches, tunnels, penstocks and various operational facilities in Tuolumne and Calaveras counties. Water for the system comes from the headwaters of the Middle Fork of the Stanislaus River and a diversion on the South Fork Stanislaus River.

The system is a complicated one, with water being moved from one watershed to another. For instance, water from Relief Reservoir and Pinecrest Lake (on different forks of the Stanislaus River) winds up at Sand Bar Dam. The dam then diverted the water to a long timber flume (later replaced with an 11-mile-long tunnel) that leads downstream to the Stanislaus Powerhouse in the Stanislaus River canyon.

Two entrepreneurs were apparently the first to envision and plan the system back around 1900. The Stanislaus Electric Power Company began actual construction of the system, with another company, the Sierra and San Francisco Power Company (SSFPC), later taking over and improving it. When the second company ran out of money, they developed a lease agreement with PG&E, which continued to develop and improve the powerhouses, dams and reservoirs with more efficient equipment as hydroelectric technology and the demand for electricity grew. Since purchasing the system in 1927, PG&E has continued to expand, improve and maintain the system.

Sand Bar Dam

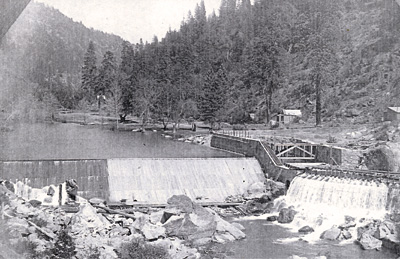

The original Sand Bar Dam was constructed in 1909 by the SSFPC. The 400-foot-long and 20-foot-high dam was five feet wide at the crest. Its granite foundation supported a rockfilled timber crib dam. The upstream slope was faced with two layers of timber planking. Ten head gates to the flume sat in a concrete wall at a right angle to the dam. These gates allowed water to enter the masonry settling basin to eliminate as much sand as possible in the flume.

Sand Bar Dam with early camp in background, 1909

When originally constructed, the dam diverted to a 78,000-foot-long timber flume perched along the southern canyon wall above the river. Maintenance of the flume required frequent replacement of timbers, a difficult task in the steep terrain. Long-term improvements were built for the production and delivery of the lumber, including a sawmill, a small railway and tramways. Eventually the flume was replaced with a tunnel, an equally difficult construction project that put an end to the constant and expensive upkeep problems.

Sand Bar Dam Camp

Over the years, there have been a number of buildings at Sand Bar Flat camp, including a lumberyard with work buildings. The first structures were likely built in 1909, when the first dam was erected. One historic photograph depicted the diversion dam and flume and at least three buildings along the flat, including a small cottage with a couple of sheds (probably a wood shed and latrine) and a shed roof structure over part of a flume.

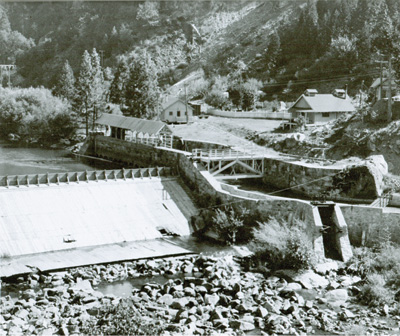

Overview of dam and camp, 1936

These early buildings were constructed by the SSFPC and included a cottage, mess hall, woodshed, a washhouse and latrines. The flume tender’s cottage (also described as the Gate Tender and Ditch Tender’s cottage), was destroyed in a fire caused by a defective flue in October 1929 and rebuilt a month later by PG&E, who had taken over operation of the entire hydroelectric system in 1927.

In 1929, a lumber yard was added to the flat just upstream from the residential camp area. This yard provided the lumber used to maintain the extensive flume. Every year before this improvement, it had been necessary to buy and deliver roughly one million board feet of lumber for the maintenance of the flume from small mills near the Stanislaus Powerhouse. PG&E consistently had a problem with the quality of their lumber as well. To remedy this situation, the Pickering Lumber Company built their railroad tracks to a point above Sand Bar Dam, making it possible to deliver lumber directly from the mill to a new siding (or spur) on the railroad. From the railroad siding, PG&E installed a 3,000-foot-long tram with a drop of 1,200 feet. This allowed PG&E to purchase higher quality Pickering lumber at a lower cost. PG&E built the tramway, as well as a 10-ton trolley hoist with gallows frame at the railroad spur and a transfer hoist at the lumber yard.

The yard included four rows of lumber stacks along a railroad track that created a loop encircling the central track. Structures at the yard included a blacksmith shop, a mill, a compressor house, a 6,000-gallon water tank, a warehouse and a latrine.

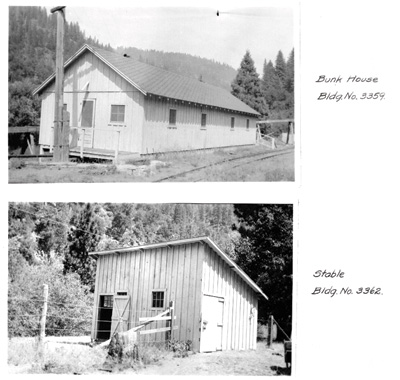

In 1930, PG&E added a bunk house to the camp for the workers at the lumber yard. Before that time, temporary workers had to live in tents at the site, which proved unsuitable during cold and wet weather. With the mill in place, it was easy for workers to build the bunk house, which measured 60 feet long by 18 feet wide, using lumber milled on site. In 1930, PG&E also installed a fire protection system at the lumberyard at the camp. A map prepared at the time depicts the “new bunk house,” “new ditch tenders cottage,” a garden area and a cookhouse grouped together at the camp and a blacksmith shop, warehouse, mill, compressor house water tank and lumber stacks around the lumber yard. A pump house and pump were also located downstream from the dam to take water from the river into the camp and lumber yard area. This water system, in conjunction with a series of fire boxes and a siren, provided the fire suppression system.

In 1936, when PG&E officially purchased the system, they inventoried the built structures and assigned numbers. PG&E used a chronological numbering system, which helps determine when the buildings were erected.

Map of Sand Bar Dam Lumberyard, 1930 (Source: PG&E 1930)

Sand Bar Dam Camp Structures in 1936

- Lumber shed (circa 1909, SSFP construction)

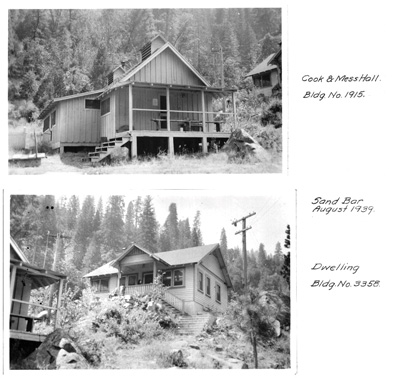

- Cookhouse and Mess Hall (circa 1909, SSFP construction), retired 1968

- Wood shed (circa 1909, SSFP construction), retired 1968

- Latrine - (SSFP construction)

- Pump house (circa 1930)

- Gate house

- Compressor house (pre-1930), abandoned in 1937

- Latrine

- Warehouse (pre-1930)

- Cottage (1929), retired 1968

- Bunk house - (1930), retired 1968

- Latrine - (circa 1929)

- Framing mill (pre-1930)

- Platform (framing mill) - (pre-1930)

- Barn (pre-1938)

- Blacksmith shop - (pre-1930)

- Bathhouse (pre-1930, SSFP construction)

- Dug-out - (pre-1938)

- Power Plant Equipment - (pre-1938)

- Saw table and frame - (pre-1930)

- Lumber racks - (pre-1930)

Photographs show a series of wood-framed buildings. The cook and mess hall likely dated to 1909. Another building from this early construction phase was the lumber shed. The bunk house and stable also had board and batten siding. The ditch (or flume) tender’s cottage constructed in 1929 was the nicest of these structures and featured Craftsman-style elements and clapboard siding.

Lumberyard buildings, including the planning mill, compressor house and warehouse, were wood frame on wood pier foundations, but had corrugated metal roof and siding materials, likely to lessen danger from fire.

Sand Bar Dam Camp showing mess hall (center left) and cottage on the hill next to the dam, 1939

Sand Bar Dam Camp, 1939, with mess hall on right and looking upstream toward bunk house, bath house and stables

The mess house was a simple wooden building. The kitchen included an ice box, a meat block, five tables, dish washing trays built into a drain board, a hot water boiler, a range and a stove and a wood burning stove. The roof had screened roof monitors to vent the heating units inside. Diners sat on benches along four wooden tables covered with oil cloth covers. Food was prepared in bulk for workers. Large No. 10-sized food cans found at the site contained fruits and vegetables, milk, coffee, spices and cooking oil or syrup. Food was prepared in cast iron pans and kettles, with mixing in enamelware bowls. Meals were served on inexpensive, durable hotel-style white improved earthenware, plain in design and undecorated.

The caretaker may have had a more “homey” atmosphere, as opposed to the basic cookhouse and mess hall. The single serving sanitary food cans may relate to an individual household cooking their own meals, away from the cookhouse.

The camp received its drinking water from a hillside spring with an intake box with pipes carrying water to the water tank. The cottage, cookhouse and bathhouses all had plumbed hot and cold running water. The cottage even had a porcelain toilet. These structures all had sewer lines as well, draining to a septic tank. Latrines supplemented camp sanitation needs for the bunk house and the lumber yard.

Little is known about the occupants of the camp. PG&E journals from the time do not provide news or updates from this little site, which was probably minor in comparison to other larger camps on the system. There are no reports of families living at the site, although it did contain a large picket-fenced garden area that was likely the domain of the cook.

After PG&E replaced the flume with the Stanislaus Tunnel in 1939, maintenance of the wooden flume became unnecessary. As a result, the lumberyard was no longer needed and the yard and camp were largely abandoned.

By 1954, the camp had become a liability. The entire camp at Sand Bar had been vacant for years and was in a very dilapidated condition. The Forest Service at the time described it as an old abandoned ghost town. The camp was being used illegally by fishermen and there was concern for fire hazard. PG&E burned the structures to the ground in early 1955, while winter snow surrounded the camp and reduced fire danger.

Today little remains at the site, with the exception of leveled building pads where camp structures used to stand. The pathways, once walked daily by dam tenders and lumbermen, still exist, traveled today by campers, fishermen and deer. The little flat at Sand Bar, now a Forest Service campground, continues to provide a nice place to spend the night along the Stanislaus River.

View Current Newsletter

View Current Newsletter